This article summarises Shamubeel Eaqub’s keynote from the Step up to the World | Tū māia ki te Ao forum 2023.

On day 2 of the Step up to the World | Tū māia ki te Ao forum on global citizenship education, economist Shamubeel Eaqub presented the opening keynote address, titled “Are we ready to navigate our changing world?”

Shamubeel’s presentation included three main themes related to economics and global citizenship of:

regime change

cultural perspectives on success

globalisation and economic dependency.

Let's look at these themes in more detail.

Regime change

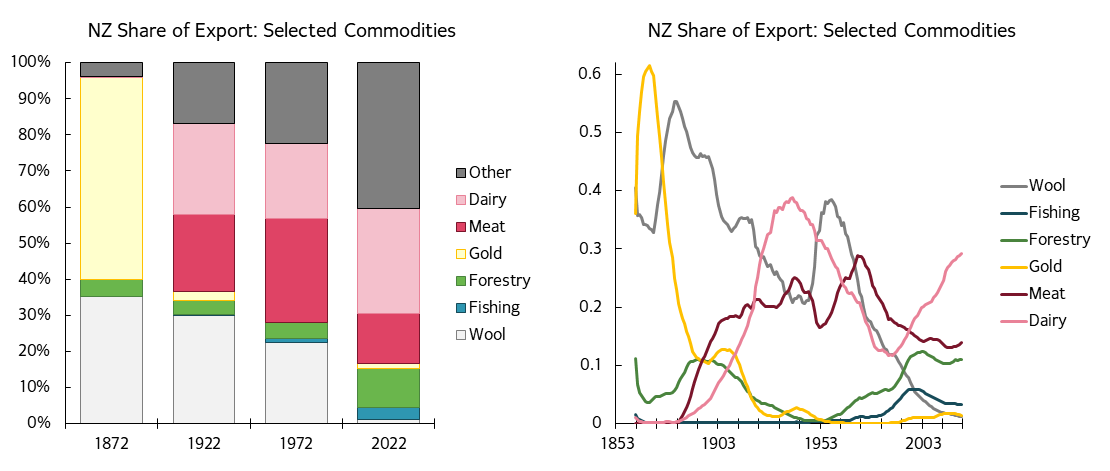

Shamubeel suggested that Aotearoa New Zealand is in the middle of a regime change. Though we’ve been engaged in the global economy for many years, our partners have changed as countries around the world shift their relationships with each other, which in turn shifts how Aotearoa relates to them through exports, imports, capital flows and people flows. For instance, the image below shows our changing export focus since 1872 where we were reliant on gold and wool exports to 2022 where our range of exports has seen gold and wool shrink while other areas begin to grow and diversify.

Since the 1800s, gross domestic product has been approximately one-third exports and one-third imports, but this has increased significantly in the last 30 years, reflecting the rise of globalisation and our increasing economic reliance on it. In Shamubeel’s view, we’re still too dependent on meat, dairy and forestry. As a nation, we’re good at those things generally, but we’re now seeing the need to think about these industries in different ways. In particular, recent weather-based damage in Tairāwhiti and Hawke’s Bay shows us that, even when we know there is an environmental cost, we still choose to prioritise short-term financial benefits.

Shamubeel emphasised the importance of actively shaping our future rather than allowing it to shape us. As global citizens, we need to have a balanced diplomatic position to allow us access to many varied economies rather than one or two powerful ones. This concept promotes the idea that individuals and society have a role to play in influencing and improving the trajectory of their environment and governance. After all, it is businesses and people that trade with each other, not countries.

Cultural perspectives on success

In working with Ngāi Tūhoe, whose ancestral land is at Te Urewera, Shamubeel recognised the contrasts and comparisons between Tūhoe and European world views of what success means. He noted that Western success, which often prioritises economic gains even if it involves environmental costs, contrasts with Tūhoe success, which values a more holistic and sustainable approach where pollution is not acceptable. This idea underscores the importance of considering diverse cultural perspectives when making policy and economic decisions – something we are uniquely positioned to achieve in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In the context of the project he was working on with Tūhoe, Shamubeel suggested that, if we take Tūhoe’s tikanga and translate it to the economy, its core principles are the same. However, how we choose to play them out are different, and this prompts us to rethink what counts as success in both worlds. Success can be different and that’s OK because world views are not always parallel.

Globalisation and economic dependency

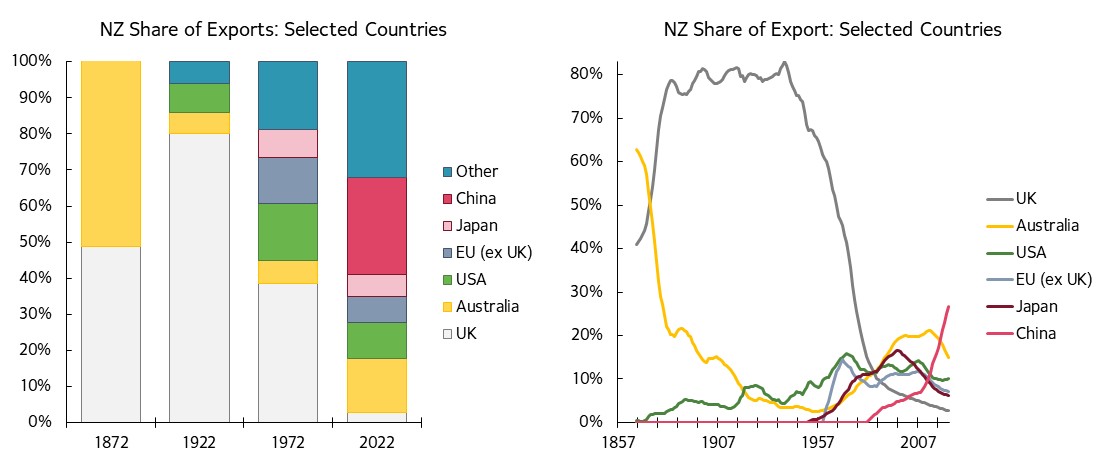

We should not think that the way the world is today is how the world will be tomorrow. History shows us that change can be evolutionary – relentless and gradual – or disruptive – rapid and abrupt. For instance, our trading partners have changed over time as shown in the image below. Where previously we traded heavily with just the United Kingdom and Australia, our partners now are spread across the globe.

These changes can be driven by our own dependence on exports, our economic priorities and shifts in global politics and economics. Our own exports have heavily relied on meat, dairy and forestry – industries that impact on, and are affected, by climate change. Shamubeel suggests that we want to have a good economy so more people are better off, so if we are to deal with change, we have to be flexible and adaptive in how we respond to change.

With ongoing realignment of geopolitics, the world is more fractured now. For example, the United Kingdom’s shift to leave the European Union and COVID-19-driven impacts that led to more working from home are changes we can choose to manage. There is no longer one central power so geopolitics are more variable. More governments around the world are acting in interventionist ways, and the spread of misinformation and disinformation has increased globally.

It is easy to give up and say everything is out of our control, but we all have a role to play. Shamubeel encourages us to be optimistic about taking control of our own direction – we can choose to shape the future or allow it to shape us. We need to find consensus and put ourselves at the centre of global change.